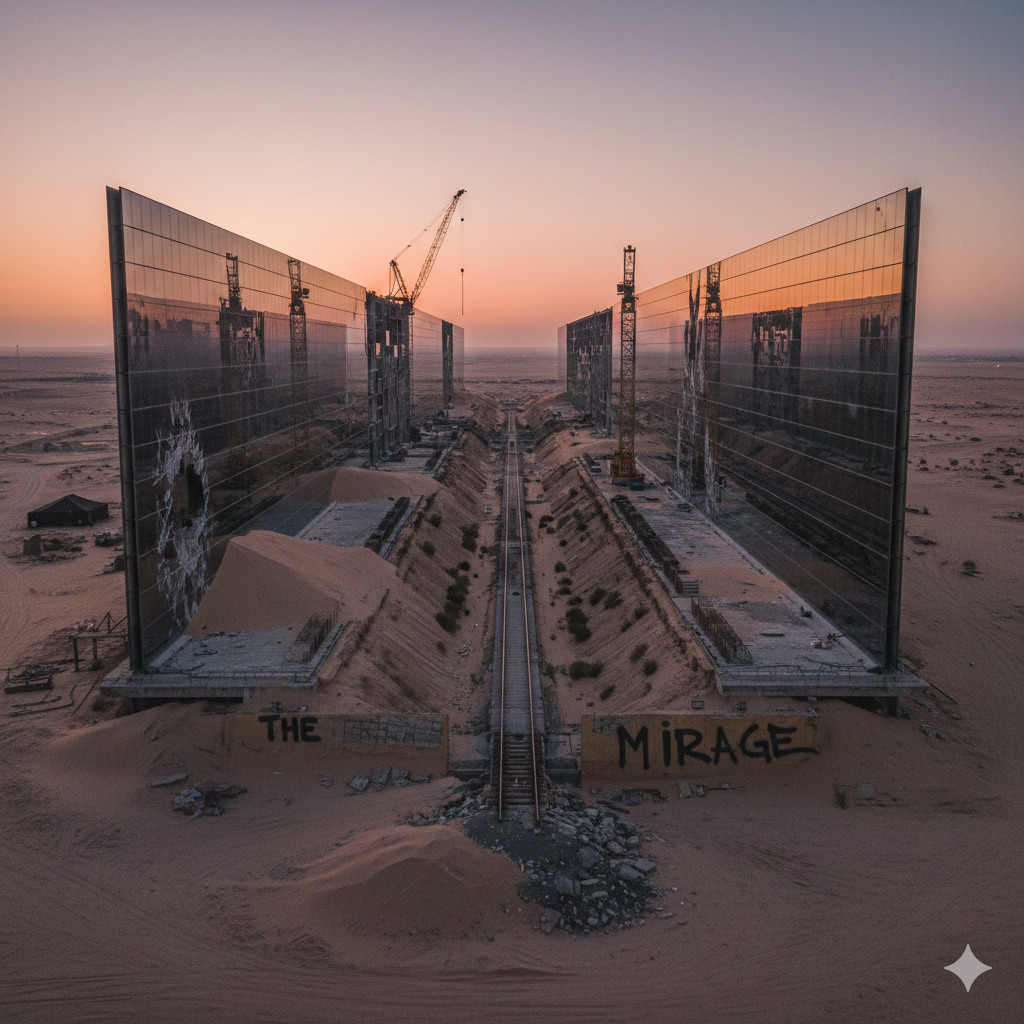

For years, the world watched with a mix of awe and skepticism as Saudi Arabia broke ground on The Line—a 170-kilometer-long, 500-meter-high mirror-walled city cutting through the Tabuk province. It was billed as the “Civilization Revolution,” a post-car, post-carbon utopia.

But as we look at the project in 2026, the mirrors are reflecting a different reality. With reports of scaled-back ambitions (from 170km down to a mere 2.4km by 2030) and shifting priorities, the project has transitioned from a blueprint for the future to a cautionary tale of architectural hubris.

Why the Mirror Cracked: The Mechanics of Failure

The “failure” of The Line isn’t just about money; it’s about the collision between hyper-idealism and physical reality.

- The Logistical Nightmare: Proponents argued that a linear city would optimize transit. In reality, a single-track high-speed rail system creates a “bottleneck by design.” If one segment fails, the entire city’s circulatory system stops. Engineers quickly realized that 3D density works better in hubs (like Tokyo or London) than in a rigid, two-dimensional line.

- The Ecological Paradox: While marketed as “sustainable,” the sheer carbon cost of the glass, steel, and concrete required to build a 500-meter wall was astronomical. Furthermore, the mirror facade acted as a lethal barrier for migratory birds and disrupted local desert thermals—proving that you cannot “protect nature” by building a massive artificial wall through it.

- The Human Scale Problem: Humans aren’t programmed to live in a 200-meter-wide canyon for their entire lives. The psychological impact of “The Trench”—where natural sunlight is a luxury and verticality replaces community—was largely ignored in the flashy CGI renders.

The Controversy: Visionary Genius or Neo-Feudalism?

This is where the debate gets heated. Some argue that The Line was never meant to be finished; it was a $1 trillion marketing campaign for Saudi Arabia’s pivot away from oil.

The Counter-Argument: Critics argue that projects like The Line are “ego-architecture”—monuments built to satisfy the whims of a single leadership rather than the needs of a population. They point to the forced displacement of the Howeitat tribe as proof that “utopias” often require dystopian methods to begin.

On the flip side, supporters claim that without such “moonshot” thinking, humanity will never break its reliance on the 20th-century urban model. They ask: If we don’t try the impossible, how will we ever discover the next “possible”?

5 Hard Lessons for the Next Mega-Project

If you are a developer, a government, or an urban planner, The Line offers a masterclass in what not to do.

| Lesson | Description | The Line’s Mistake |

|---|---|---|

| Iterative over Absolute | Build in phases that can stand alone. | The Line required total completion to function as intended. |

| Human-Centric Design | Start with how people move and feel. | It started with a “cool shape” and tried to fit humans inside it. |

| The “Reality Check” | Physics doesn’t care about your vision board. | Ignored the thermal expansion of glass and wind-tunnel effects. |

| Financial Transparency | Infinite budgets are a myth. | Underestimated the drain on the Public Investment Fund (PIF). |

| Social License | A city needs a soul, not just residents. | Failed to account for the organic growth that makes cities “alive.” |

The Verdict: A Monument to the “Could Have Been”

The Line isn’t a total loss—it has pushed the boundaries of modular construction and desalination technology. However, as a functional city, it has become a “vertical ghost town” in the making. It serves as a reminder that technology should serve the city, not the other way around.

We are entering an era of “Reflective Urbanism.” The next great cities won’t be glass walls in the desert; they will likely be “Sponge Cities” that absorb rainwater, or “15-Minute Cities” built within existing ruins. The future isn’t a line; it’s a circle—cyclical, adaptive, and humble.