In the global theater of 21st-century prestige, there is no stage more dazzling—or more dangerous—than hosting a mega-event. Whether it is the Olympic Games or the FIFA World Cup, the narrative sold to taxpayers is almost always the same: a temporary investment for a permanent legacy of prosperity. Proponents promise a “catalytic effect”—surging tourism, modern infrastructure and a global “Rebranding” that will attract foreign investment for decades.

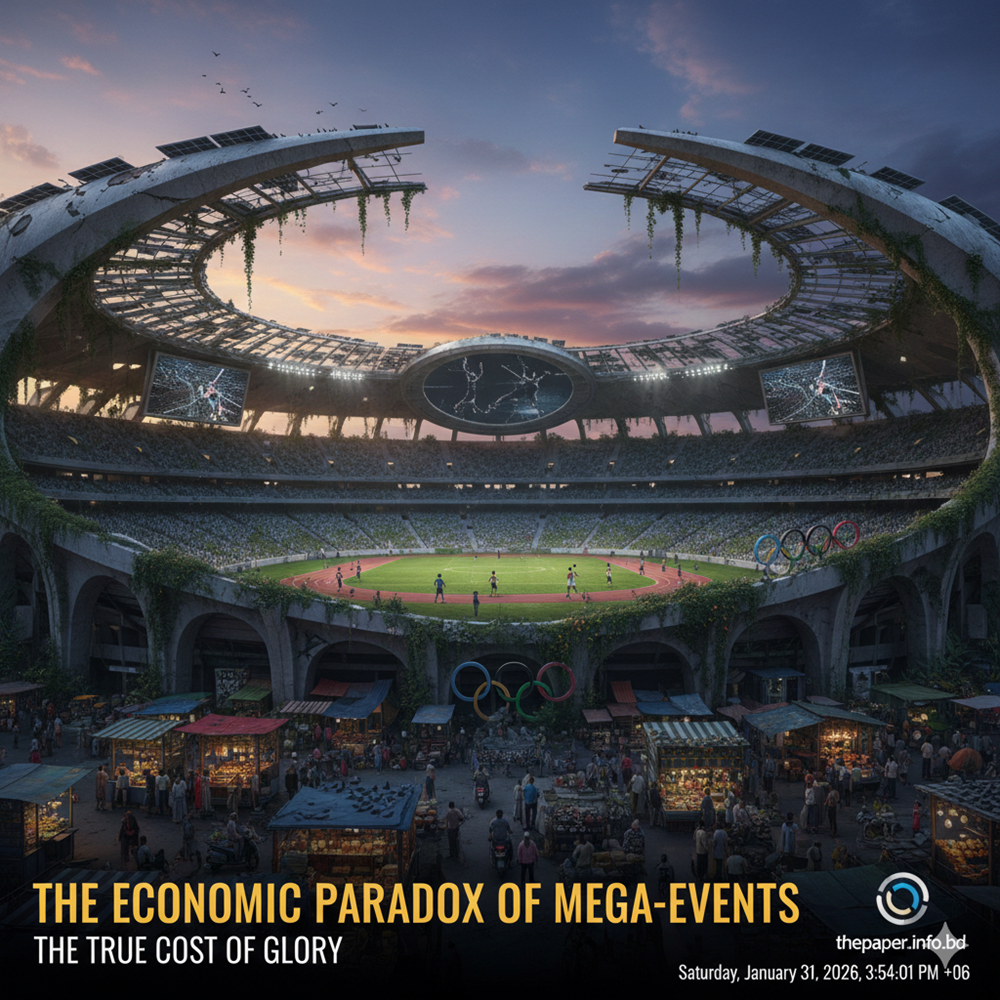

Yet, a stubborn paradox remains. While these events are marketed as economic engines, history is littered with host cities that find themselves financially stalled. From the crumbling venues of Rio 2016 to the decades-long debt odyssey of Montreal 1976, the “Economic Paradox” of mega-events suggests that the very scale required to host the world is often the scale that guarantees a local deficit.

The “White Elephant” Syndrome

The most visible symptom of this paradox is the “White Elephant”—colossal, state-of-the-art stadiums built for a few weeks of glory that eventually become multi-million dollar maintenance liabilities. In 2026, this issue has reached a breaking point. For a city to host an 80,000-seat athletic event, it must meet stringent international standards that often bear little relation to the daily needs of the local population.

Economists refer to this as the “over-specification trap.” In the bid phase, cities promise the world’s most advanced facilities to outcompete rivals. Once the torch is extinguished, however, the host is left with specialized infrastructure that has no sustainable tenant. In many developing nations, the electricity and resources diverted to maintain these vacant monuments are stripped away from essential public services like schools and hospitals, turning a symbol of progress into a drain on social welfare.

The Myth of the “Tourist Windfall”

The second pillar of the paradox is the “Crowding Out” effect. Organizers often cite massive projected visitor numbers as a guaranteed ROI. However, longitudinal studies reveal a more complex reality. While sports fans do flood the city, they frequently displace regular business travelers and traditional tourists who wish to avoid the hiked prices, crushing crowds, and heightened security.

Furthermore, the “leakage” of revenue is significant. During a World Cup, hotel room rates may quadruple, but those profits rarely stay in the host city. Instead, they flow toward international hotel chains and global sponsors. For the local street vendor or small-business owner, the increased costs of security and logistics often outweigh the marginal increase in foot traffic. By the time the final whistle blows, the “net” increase in economic activity is often statistically invisible or, worse, negative when adjusted for public spending.

The Winner’s Curse and the Bid Trap

Why do cities continue to bid if the numbers don’t add up? This is known as the “Winner’s Curse.” In a competitive bidding environment, the city that wins is often the one that most grossly overestimates the benefits and underestimates the costs.

In 2026, the cost of just bidding can exceed $100 million. This high barrier to entry creates a selection bias where only the wealthiest nations or those with specific political agendas (see: Sportswashing) can afford to participate. This has led to a “Bidding Paradox”: as the public in democratic nations becomes more aware of the “Mega-Event Syndrome,” they are increasingly voting “No” in referendums. This leaves the field open to autocratic regimes or “Sovereign Wealth” states that prioritize international prestige over immediate domestic return on investment.

A New Model: Sustainability or Irrelevance?

Is there a way out of the paradox? As we look toward the next cycle of global games, a new “sustainable hosting” model is beginning to emerge. The 2026 World Cup, distributed across the U.S., Mexico, and Canada, is an experiment in “burden sharing.” By using existing infrastructure and spreading the logistical load across an entire continent, these nations hope to capture the soft-power benefits without the catastrophic debt of a single-city host.

Furthermore, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has introduced “Agenda 2020+5,” encouraging hosts to use temporary structures and existing venues, even if they are in different cities. The goal is to move away from “edifice-building” and toward “experience-hosting.”

Conclusion: The True Cost of Glory

The economic paradox of mega-events reminds us that glory is rarely free. For a host city, the true measure of success is not how brightly the fireworks explode on opening night, but how the city functions five years later. If the infrastructure serves the citizen as well as it served the athlete, the paradox is solved. But if the legacy is merely a skyline of empty concrete shells and a ledger of red ink, the mega-event remains a “poisoned chalice”—a brief moment of global attention bought at the price of local stability.

As the world becomes more fiscally cautious, the era of “stadiums at any cost” may be coming to a close. The future of sports will belong to those who can prove that a game is not just a spectacle, but a smart, sustainable investment in the human fabric of the city.